Fair Trial Rights in Cambodia Monitoring at the Court of Appeal

Publication Year: 2014 / Sources: Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR)The functioning of the judiciary has been among the major human rights concerns in Cambodia for some time, central as it is to the protection and enforcement of other rights and the establishment of the rule of law. Although there have been steady improvements in the adherence to some of the procedures that underpin fair trial rights within the Cambodian judiciary, many areas of concern remain. One of the major issues that impacts upon fair trial rights in Cambodia is the lack of separation of powers and the continued influence that the executive exert on the judiciary.

CCHR’s Trial Monitoring Project (the “Project”) has collected data from the monitoring of 204 criminal trials at the Court of Appeal between 1 March 2013 and 31 January 2014 (the “Reporting Period”) in order to assess its adherence to fair trial rights as set out in international and Cambodian law. The Report presents and analyzes the data collected during the Reporting Period.

Justice for the Survivors and for Future Generations

Publication Year: 2010 / Sources: ADHOC, Extraordinary Chambers (EC), International Criminal Court (ICC)The ECCC / ICC Justice project, built on ADHOC’s and its partners’ strengths, has fulfilled and surpassed its goals. It has promoted justice for the victims of the Khmer Rouge regime by (1) dramatically influencing the shape and course of the Khmer Rouge Trials and (2) animating a sustained, nation-wide debate on Khmer Rouge crimes. Complementary project activities around the ICC were somewhat clouded by the urgency and prominence of ECCC- related work; nevertheless they constituted a key input to integrating the Rome Statute into Cambodian law.

Three Draft Laws Relating to the Judiciary

Publication Year: 2014 / Sources:One of the fundamental principles of a democratic state is the principle of seperation and independence of powers between the legislative, executive and judiciary. Independence of the courts is a key element of the rule of law and guarantees fair hearings. As such, the 1993 Constitution of the Kingdom of Cambodia (the “Constitution”) establishes the independence of the judiciary and guarantees the principle of the separation of powers. Independence means being free from control or influence. In this reguard, the judiciary is independent when it can functions separately from the legislative and executive. The judiciary should be protected from inappropriate interference and influence, as the judiciary also checks and balance the powers of the executive and legislative. According to the three drafts laws, namely the draft Law on the Organization and Functioning of the Supreme Council of the Magistracy (the “SCM”), the draft Law on the Statute of Judges and Prosecutors, and the draft Law on the Organization and Functioning of the Courts, it is the King, with the assistance of the SCM, who guarantees the independence of the judiciary.

This legal analysis is conducted with an aim to examine the scope of powers of the legislative and executive bodies as enshrined in the three draft laws concerning the judiciary.

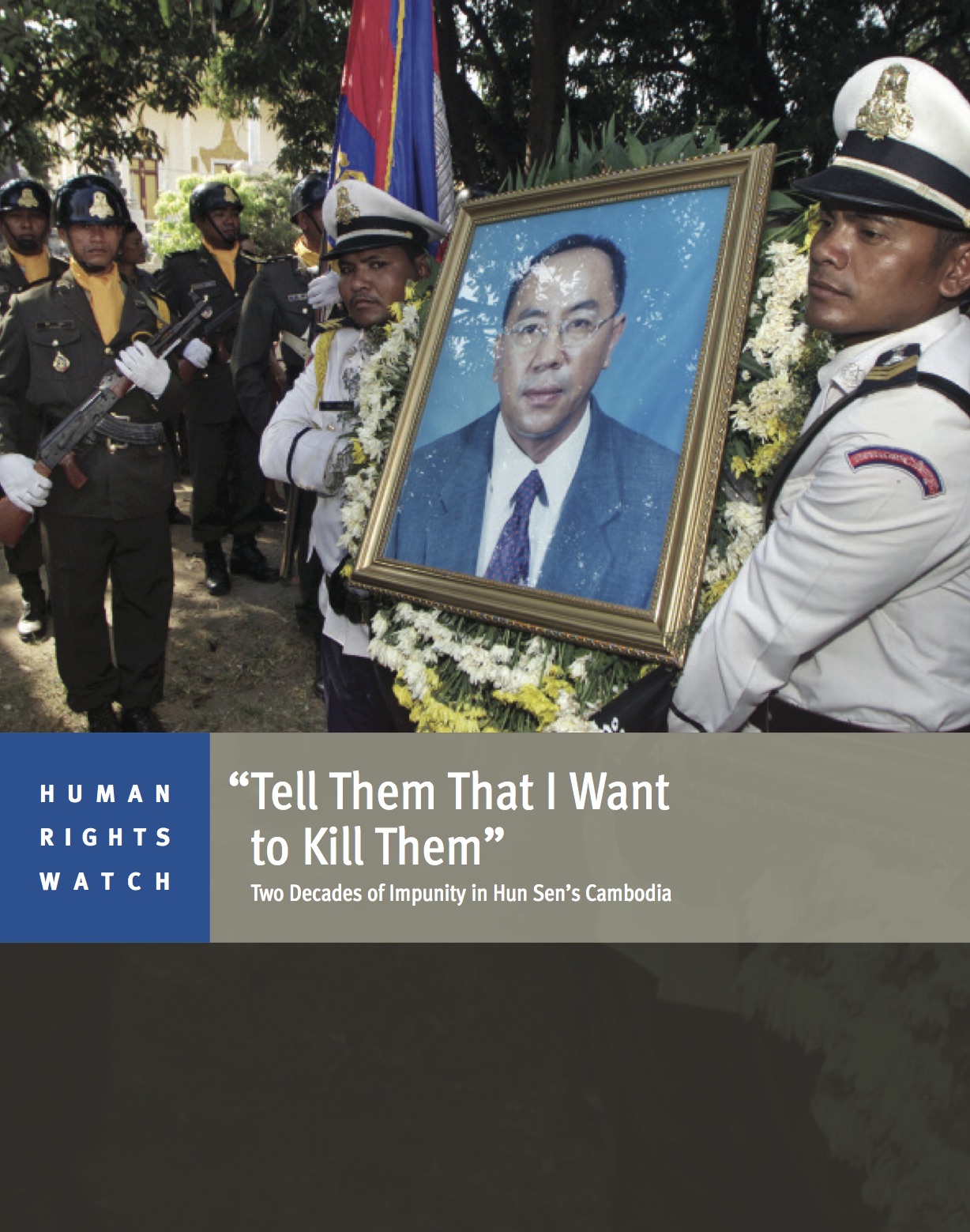

“Tell Them I Want to Kill Them”: Two Decades of Impunity in Hun Sen’s Cambodia

Publication Year: 2012 / Sources: Human Rights WatchKillings, torture, illegal land confiscation, and other abuses of power are rife around the country. More than 300 people have been killed in politically motivated attacks since the Paris Agreements. In many cases, as with members of the brutal “A-team” death squads during the UNTAC period and military officers who carried out a campaign of killings after Hun Sen’s 1997 coup, the perpetrators are not only known, but have been promoted. Yet not one senior government or military official has been held to account. Even in cases where there is no apparent political motivation, abuses such as extrajudicial executions, torture, arbitrary arrest, and land grabs almost never result in successful criminal prosecutions and commensurate prison terms if the perpetrator is in the military, police, or is politically connected. It is no exaggeration to say that impunity has been a defining feature of the country since the signing of the Paris Agreements. To illustrate the problem, this report details some cases of extrajudicial killings and other abuses that have not been genuinely investigated or prosecuted by the authorities [we have focused on some cases, but could have included many others as the examples are vast].

Law on Anti-Corruption (the “Law”)

Publication Year: 2011 / Sources: CCHR Law Review Series, 2011This fact sheet provides an overview of the key concerns relating to the Law, particularly in the context of the widespread corruption in Cambodia. This fact sheet is written by CCHR, a non-aligned, independent, non- governmental organization that works to promote and protect democracy and respect for human rights – primarily civil and political rights – throughout Cambodia.

Justice and Judicial Corruption

Publication Year: 2007 / Sources: Magazine of the Documentation Center of CambodiaJustice in Cambodia is again in jeopardy after the recent publication of a scathing audit of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC). The audit-prepared by the UN Development Program (UNDP), which administers $6.4 for the tribunal-accused Cambodian officials on the ECCC of improper recruitment, unwarranted salary increases, and general mismanagement of court operations. The auditors’ conclusion was blunt: if the tribunal fails to enact appropriate reforms, the UNDP should consider pulling out. Cambodian officials have acknowledged “mistakes” but argue that those mistakes do not warrant scrapping the trials altogether. After a decade of arduous negotiations, international officials are also not eager to return to the bargaining table and defer justice once again.

Global Corruption Report 2007: Corruption in Judicial Systems

Publication Year: 2007 / Sources: Transparency InternationalIt is difficult to overstate the negative impact of a corrupt judiciary: it erodes the ability of the international community to tackle transnational crime and terrorism; it diminishes trade, eco- nomic growth and human development; and, most importantly, it denies citizens impartial sett- lement of disputes with neighbours or the authorities. When the latter occurs, corrupt judiciaries fracture and divide communities by keeping alive the sense of injury created by unjust treatment and mediation. Judicial systems debased by bribery undermine confidence in governance by facilitating corruption across all sectors of government, starting at the helm of power. In so doing they send a blunt message to the people: in this country corruption is tolerated.