Existence and Use of Phones that permit written communication in Khmer Script

Publication Year: 2013 / Sources: Open Institute (Phong Kimchhoy, Uy Sareth, Javier Sola)This study responds to the need to understand if SMS can be used as a tool for government and civil society organizations to communicate directly with citizens and beneficiaries all over Cambodia, offering to them information and services in Khmer through mobile phones. It also attempts to understand if smart phones are or will become a key device for accessing Internet and social media in Cambodia, as these networks are quickly becoming the main source of information for youth.

Download: English | Khmer

Internal Migration for Low-skilled and Unskilled Work in Cambodia: Preliminary Qualitative Results

Publication Year: June 2016 / Sources: Open InstituteIn order to propose solutions to reduce the disconnect between the national demand for unskilled and low-skilled employment and potential national workers, it is first necessary to undertake qualitative research with the following objectives:

1. To have a preliminary understanding of the structure of the main sectors that absorb national migration: garment, construction, hospitality and security

2. To have a preliminary understanding of the present hiring process of local Cambodian employers in the targeted sectors

3. To have a preliminary understanding of internal migration paths and practices

Internal Migration Patterns and Practices of Low-skilled and Unskilled Workers in Cambodia

Publication Year: Sep, 2016 / Sources: Open InstituteThe data shows that there is constant availability of work all year round in the sectors of Manufacturing, Construction, Hospitality and Security, with a peak of labor demand after the two main holidays. The main and most effective method of communication used by companies to find new employees is to communicate the job opportunities to their existing workers, who relay this information to potential workers who might be interested. HR managers are nevertheless technology-savvy and they are open to use electronic channels to find new workers.

The main conclusion is that, while a clear mechanism for accessing low-skilled and unskilled employment exists in Cambodia based on the trust relationships between potential migrants and family members and friends who are already working, this

mechanism is not sufficient to meet the demand for unskilled and low-skilled labor in the country, nor does it provide work in Cambodia to all potential migrants who would prefer to work in their own country. A significant portion of cross-border migration is most probably motivated by this disconnect.

Youth in Cambodia: A Force for Change

Publication Year: 2008 / Sources: Pact CambodiaMore than half the population of Cambodia is less than 20 years old, and youth comprise almost 20% of the total population. Unlike some countries in Southeast Asia where this percentage is expected to decline by 2030, the proportion of youth in the population is expected to peak in 2035 with average annual growth of 0.1% in 2005-2015 and 1.0% in 2025-2035.

Download: English | Khmer

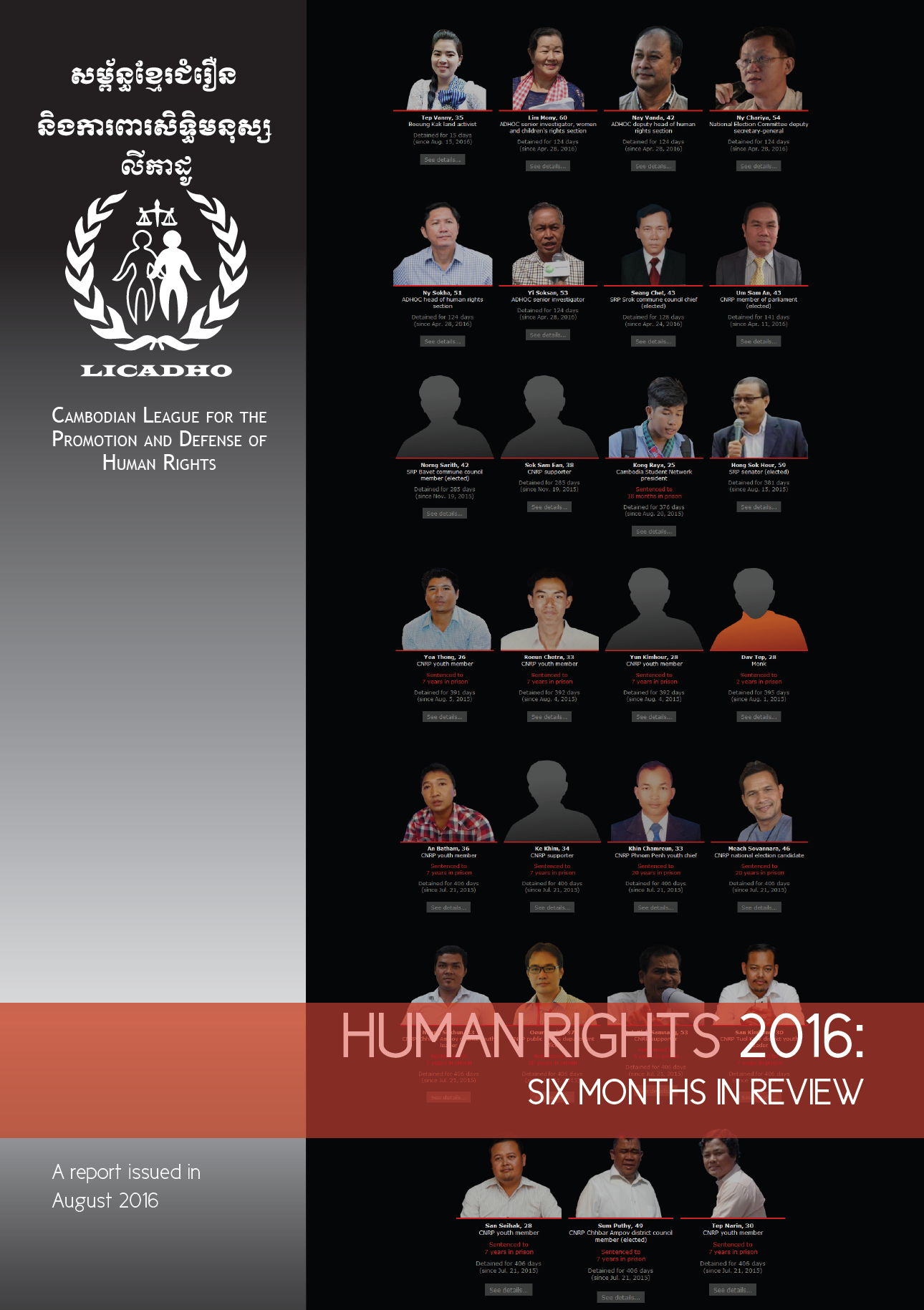

Human Rights 2016: Six Months in Review

Publication Year: August 2016 / Sources: LICADHOThis is the Human Rights Report in 2016 within first six months monitored by LICADHO.

Download: English | Khmer

ILO Policy Brief on Youth Employment in Cambodia

Publication Year: 2007 / Sources: International Labor Organization (ILO)Cambodia has a young population with 39 per cent of the population in 2004 below 15 years of age, down from 43 per cent in 1998. By 2004 the dependency ratio showing the children and elderly as a percentage of the intermediate group was 74 per cent.1 Youth aged 15–24 represented 22 percent of the population that year. Large numbers of young people are entering

the labour force as a result of a baby boom in the 1980s. Measures must be taken to ensure that youth do not add to underemployment in the countryside or lead to higher rates of urban unemployment but instead contribute to growth and development through productive employment.

2014 Post-UPR National Consultation Outcome Report

Publication Year: 2014 / Sources: Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR)This Outcome Report summarizes presentations, panel discussions and small group discussions undertaken during the 2014 Post-Universal Periodic Review National Consultation organized by CCHR and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (“OHCHR”) in Cambodia.

Download: English | Khmer

Youth in Cambodia

Publication Year: 2002 / Sources: Forum Syd CambodiaThis report focuses on youth as a specific group. There is no legal definition for youth (nor for children or adults) in Cambodia, but the responsible Department under Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports defines youth as people between 14 and 30 years old. The aim of the study is to map out youth organisations and activities in Cambodia. It also provides some information regarding the general situation for young Cambodians and youth policy from the Government and the major donor agencies.

Download: English | Khmer

Skin on the Cable: The Illegal Arrest, Arbitrary Detention and Torture of People who use Drugs in Cambodia

Publication Year: 2010 / Sources: Human Rights Watch“Skin on the Cable”

The Illegal Arrest, Arbitrary Detention and Torture of People Who Use Drugs in Cambodia

Cambodians who use drugs confound the notion that drug dependence is a self-inflicted condition that results from a character disorder or moral failing. When Human Rights Watch talked with these people, they were invariably softly spoken and polite. They talked openly and honestly about difficult childhoods (in many cases still underway) living on the streets, or growing up in refugee camps in Thailand. Often young and poorly educated, they spoke of using drugs for extended periods of time. Despite many hardships in their lives, their voices rarely became bitter except when describing their arrest and detention in government drug detention centers. They did not mince words when describing these places. One former detainee, Kakada, was particularly succinct: “I think this is not a rehab center but a torturing center.

Download: English | Khmer

Human Trafficking Vulnerabilities in ASIA: A Study on Forced Marriage Between Cambodia and China

Publication Year: 2016 / Sources: United Nations Action for Cooperation against Trafficking in Persons (UN-ACT)Human Trafficking Vulnerabilities in ASIA:

A Study on Forced Marriage Between Cambodia and China

This report examines patterns of forced marriage in the context of broader migratory flows between Cambodia and China. It primarily draws on the accounts of 42 Cambodian women who experienced conditions of forced marriage, with interviews having taken place in both countries. Key informants from government and non-government stakeholders in Cambodia and China were consulted as well.

The objective has been to analyze recruitment, brokering, transportation and exploitation patterns as well as the links between these; to determine service needs amongst Cambodians trafficked to China for forced marriage, in China, during the repatriation process and upon return to Cambodia; as well as to identify opportunities for interventions to prevent forced marriages from occurring and to extend protective services to those in need, at both policy and programming levels.