Cambodia’s Development Dynamics: Past Performances and Emerging Priorities

Publication Year: 2013 / Sources: Cambodia Development Resource Institute (CDRI)This Report analyses Cambodia’s development dynamism over the last two decades and identifies emerging development priorities for the next two. It examines Cambodia’s past performance, emerging priorities and future challenges in economic, social, environmental and political spheres.

Report on the Voter Registry Audit (VRA) in Cambodia

Publication Year: 2013 / Sources: National Democratic Institute (NDI)Exercising the fundamental right to vote in most countries depends largely on the existence of an accurate and complete voter registry. The maintenance and upkeep of such a voter registry can be particularly challenging in countries with insufficient records, transient populations or weak infrastructure. Moreover, voter registries are susceptible to manipulation for electoral advantage. Inaccurate voter registries have led to numerous post-election conflicts in elections held around the world and have disenfranchised many eligible voters. In Cambodia, some political parties and civil society groups have expressed concerns about the accuracy of the voter registry and a lack of confidence in the registration process. Verification of the accuracy of a voter registry through a voter registry audit (VRA) can help to detect and deter electoral fraud, correct administrative errors, and promote broad public confidence in the process on election day and beyond.

National Assembly Candidate Debates

Publication Year: 2013 / Sources: National Democratic InstituteCandidates competing in the 2013 National Assembly election vied for voter support in a series of debates sponsored by the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI) from July 7 to July 20, 2013. The aim of the debates was to have a constructive dialogue of ideas and opinions among current and potential policy makers, so that citizens could judge their options and make an informed choice on election day. Though the debates took place in a tense political environment, and in spite of the bureaucratic challenges and reluctance of some parties to participate at the outset, the program successfully reached this goal. The ruling party and main opposition party were on stage together several times, including on television; more than 16,000 people attended the debates in person; and broadcasts went as planned on numerous media outlets, potentially reaching millions of voters.

Cambodia Diversifying Beyond Garments and Tourism

Publication Year: 2014 / Sources: Asian Development Bank (ADB)Rapid economic expansion brought important gains in national income and poverty reduction. Even so, Cambodia remains one of Asia’s eight low-income countries and the second-poorest country in Southeast Asia. It also faces considerable challenges in building a modern, sophisticated, and vibrant economy, and to raise living standards to the levels of its more developed neighbors. To sustain its strong economic performance, several growth-supporting factors must be strengthened—infrastructure remains inadequate and unreliable, education attainment and skills are subpar, governance is weak, and savings rates are still low.

This study suggests that Cambodia needs to address these highly interrelated weaknesses to avoid getting trapped in low-wage, low-value-added production, and to maintain a stable political environment that is conducive to investment and commerce. Moving into higher-value-added production and climbing the global value chain will require sustained improvements in infrastructure, human capital, governance, and other economic factors.

Report on Constituency Dialogues in Cambodia

Publication Year: 2013 / Sources: National Democratic Institute (NDI)The National Democratic Institute (NDI or the Institute) has organized multiparty constituency dialogues (CDs) since 2004 with elected representatives in the National Assembly (NA) from all political parties. These dialogues aim to enhance MNAs’ knowledge of and relations with their constituencies and educate citizens on the roles and responsibilities of an MNA in a democratic society. Another important goal of the program is to increase citizens’ understanding of their political options, as there are limited opportunities for them to hear alternative viewpoints and policies from non-ruling parties. Finally, the CDs aim to normalize and demonstrate the importance of debate in Cambodia, where policy exchanges between political opponents are rare and viewed with caution.

Cambodia: Getting Away with Authoritarianism?

Publication Year: 2005 / Sources: Journal of Democracy, Volume 16Since Cambodia’s 1993 constitution stipulates that a two-thirds parliamentary majority is needed to form a government, the parties had to bargain in the election’s wake. Bargain they did, for 11 long months. All during this time Cambodia had no properly constituted government, but little changed. Power remained firmly in the hands of the CPP, which has ruled since the 1980s, initially under Vietnamese tutelage. It has such a tight grip that elections have become little more than a side- show, helping to bolster the electoral-authoritarian regime that Hun Sen has built.

Cambodia Gagged: Democracy at Risk?

Publication Year: 2010 / Sources: Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR)This Report provides an analysis of the situation of freedom of expression in Cambodia since the Joint Submission. Many of the events discussed herein have been widely reported. Therefore, in the course of our research we have used a number of media sources including The Phnom Penh Post, The Cambodia Daily, Radio Free Asia and Voice of Democracy and other relevant news websites. In the course of preparing our analysis we examined data collected and compiled by the participating civil society organisations, through our respective monitoring, research, investigation and other fieldwork activities…

This Report is not intended to be a comprehensive quantitative report on the situation of freedom of expression in Cambodia, and therefore the cases described are not an exhaustive account of all violations of freedom of expression since the Joint Submission. Rather the cases used are a sample of a broader pattern of violations, with the Report providing a qualitative analysis of the situation of freedom of expression in Cambodia.

Cambodian Corruption Assessment

Publication Year: 2004 / Sources: USAID, Casals & AssociatesEarly in 2004, USAID/Cambodia began planning an assessment of corruption in Cambodia. The Statement of Work noted the unfortunate reality that corruption has become part of everyday life in Cambodia, that in fact it has reached “pandemic” proportions. USAID/Cambodia requested an assessment focused around several topical areas. For example: What are the prevailing forms of corruption? Is the Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC) taking useful steps? Who are the winners and losers? What are the roles of civil society, the media and private business? The Assessment Team was also invited to recommend activities that offer a reasonable chance of success in increasing Royal Cambodian Government (RGC) transparency and accountability, while beginning to reduce systemic corruption. USAID recruited a three-member team to undertake the assessment.

Beyond Capacity: Cambodia’s Exploding Prison Population & Correctional Center

Publication Year: 2010 / Sources: LICADHOCambodia’s prison population is in the midst of an unprecedented population boom. Just six years ago, the 18 prisons monitored by LICADHO were at roughly 100% of their collective capacity1. Since then, the population has exploded, growing at an average rate of 14% per year. Prison capacity has also increased, but not nearly enough to keep pace with growth. The General Department of Prisons (GDP) reported in March 2010 that the entire prison system held 13,325 inmates – 167% of the system’s 8,000-inmate capacity. The 18 prisons LICADHO monitors, meanwhile, were filled to 175% of capacity as of June 2010. As of December 2009, one third of all Cambodian prisoners – over 4,000 – were in pretrial status.

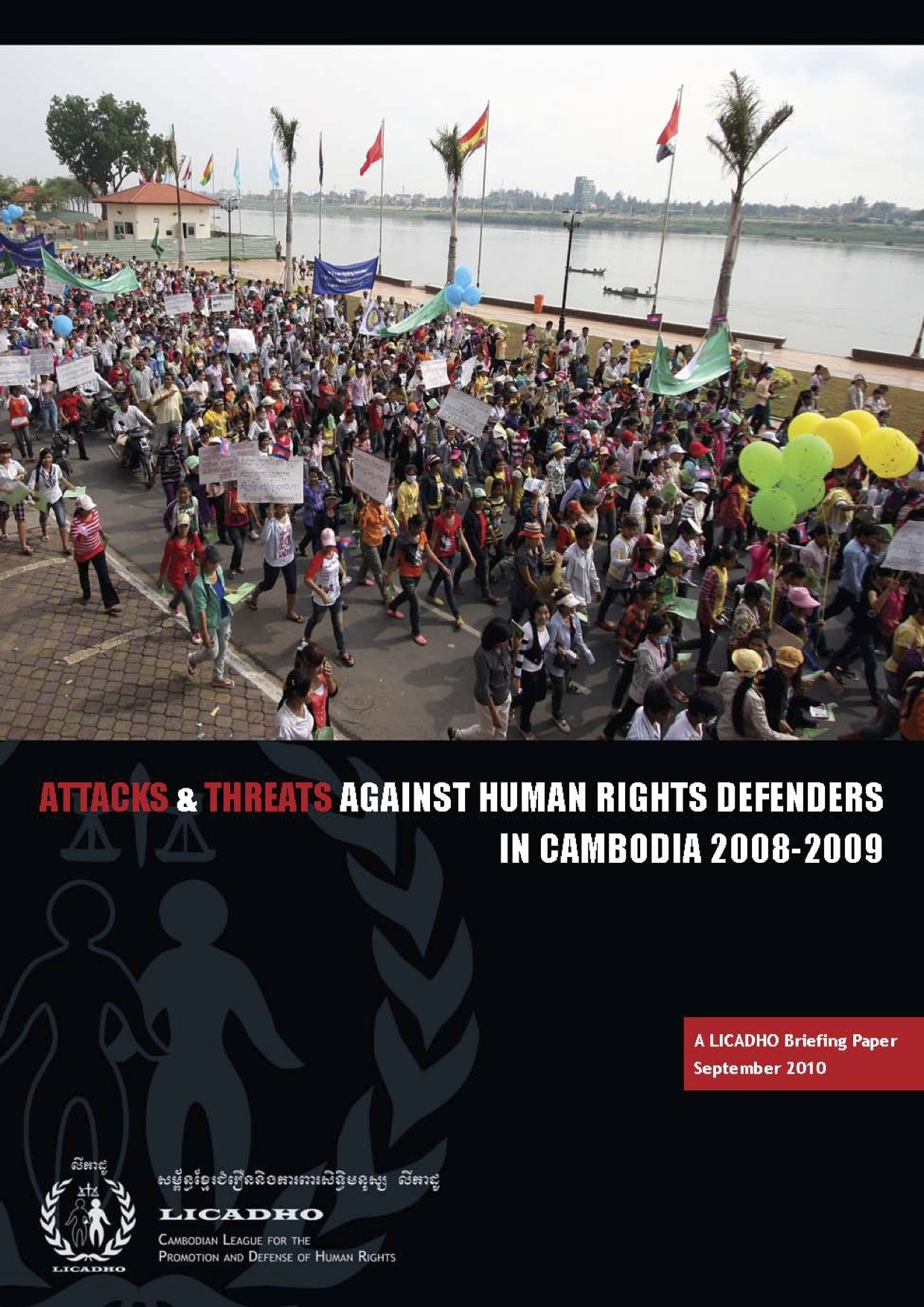

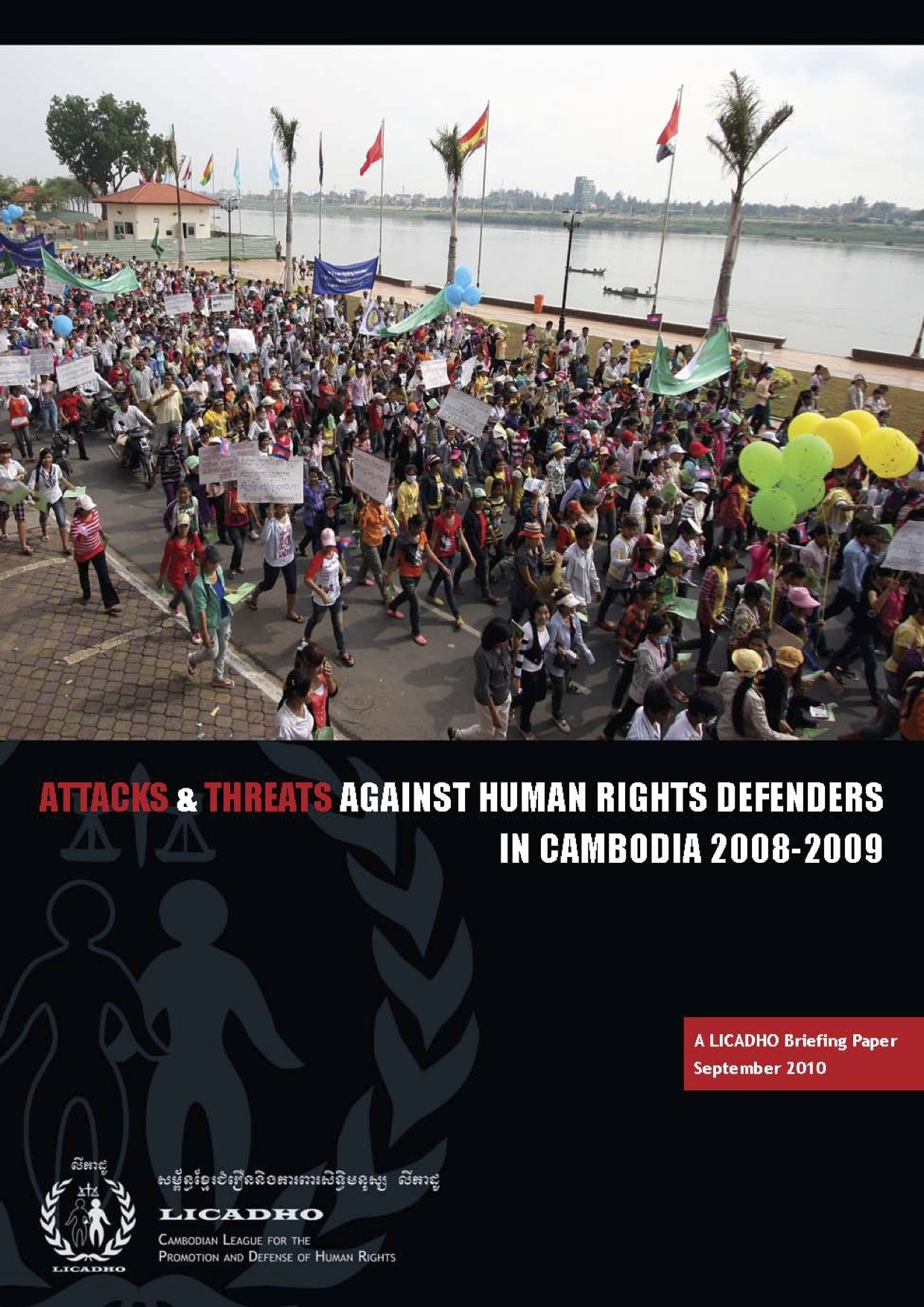

Attacks & Threats Against Human Rights Defenders in Cambodia 2008-2009

Publication Year: 2010 / Sources: LICADHOThis account is by no means a comprehensive examination of all of the attacks and threats against human rights defenders in Cambodia in the last two years, as many instances go unreported. Instead the report aims to provide a concise overview of the human rights abuses that LICADHO observed and investigated in 2008 and 2009. It also serves as a reference tool to address the attacks and threats against human rights defenders, and raise awareness about the state of human rights in Cambodia since 2007.