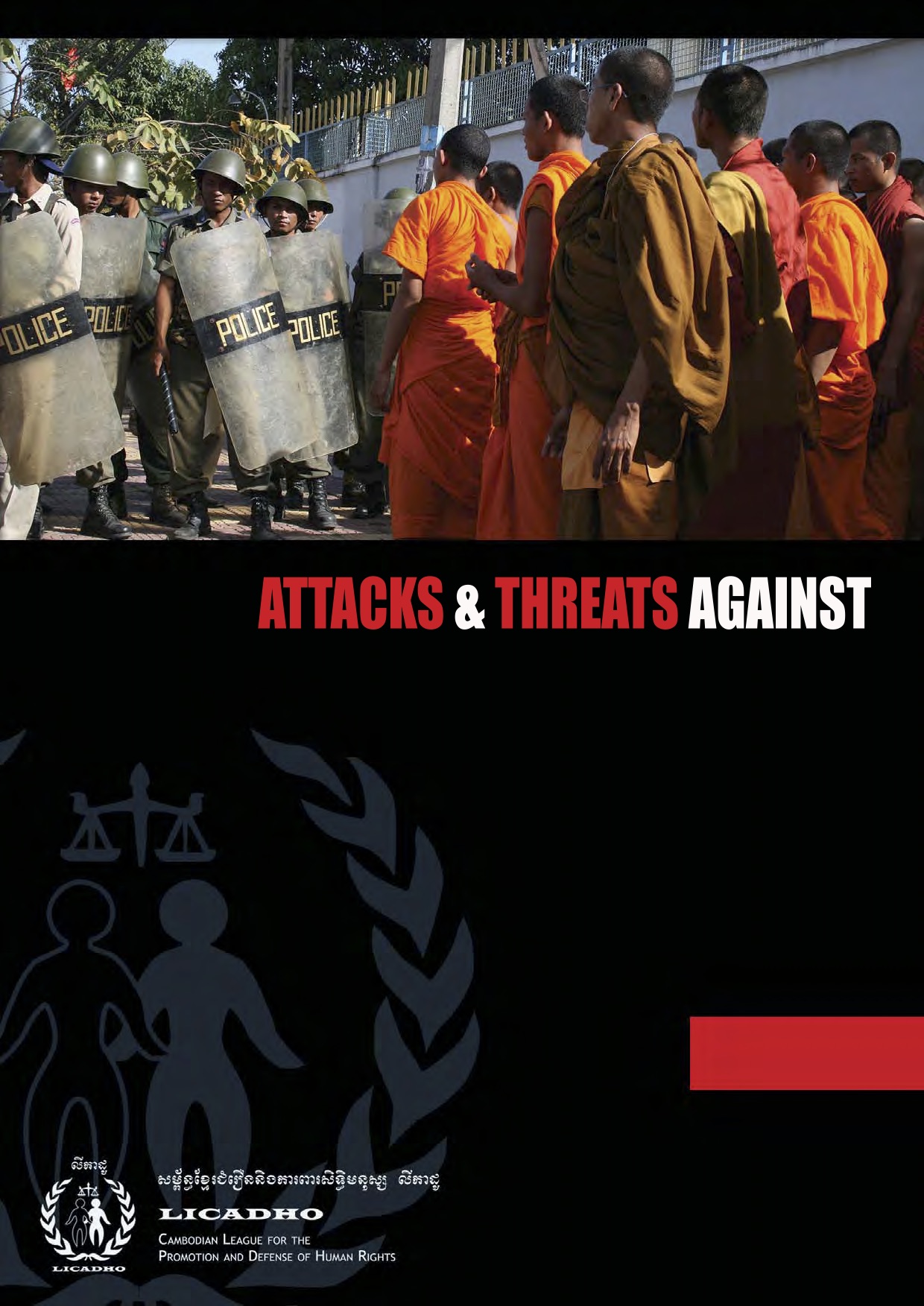

Attacks & Threats Against Human Rights Defenders in Cambodia 2007

Publication Year: 2008 / Sources: LICADHOCambodia is a dangerous place for human rights defenders. During 2007, the Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (LICADHO) recorded more cases than ever before of threats and attacks against activists attempting to peacefully defend the rights of others.

Throughout 2007, the patterns of threats and attacks against human rights defenders observed in previous years have continued and intensified. Representatives of communities engaged in disputes over land and housing were targeted with threats, unwarranted criminal charges, and in some cases imprisonment. Trade union leaders were assaulted, arrested and prosecuted for their legitimate union activity; one such leader was murdered. Human rights NGO workers continued to be threatened and obstructed in carrying out their work, whilst private citizens legitimately assisting asylum seekers were harassed and imprisoned.

Assessment of the Enabling Environment for Civil Society

Publication Year: 2013 / Sources: Cooperation Committee for Cambodia (CCC)Civil societies are not only shaped by the legal and regulatory frameworks, but by the economic, political, cultural, religious and social environments in which they operate. A full assessment of the environment in which civil societies operate would examine all these dimensions – economic, political, cultural, religious and social – in an effort to promote understanding of the potential and success of civil society. This report focuses on the legal, regulatory, and policy environment in which civil society organisations (CSOs) operate, as this is key to their ability to register, operate, access resources, and effectively engage in advocacy, all of which in turn contributes to civil society’s ability to flourish and be successful.

Is the Trial of ‘Duch’ a Catalyst for Change in Cambodia’s Courts?

Publication Year: 2010 / Sources: East-West CenterAt his trial under an international hybrid tribunal, the notorious member of the Khmer Rouge regime Kaing Guek Eav, known as “Duch,” admitted to being responsible for the deaths of more than 12,000 people between 1975 and 1979. This admission and expected conviction (the only real question left is the level of punishment) signify a symbolic victory for the Cambodian people. It is important for Cambodia’s healing that the people know their history and believe that there can be justice. The coverage of Duch’s trial and associated community outreach have engaged the public in the process and have increased education about the country’s recent past. But whether the hopes that the hybrid tribunal in which his trial was conducted may serve as a model for a more transparent system of justice — as opposed to the endemic system of patronage and corruption that is the norm for Cambodia’s judiciary and law enforcement — has yet to be seen. For these hopes to be realized, the educational outreach, and the pursuit of judicial reform must continue.

Annual Development Review 2013-14

Publication Year: 2014 / Sources: Cambodia Development Resource Institute (CDRI)Cambodia is rapidly changing – economically, socially and politically. With an average annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of about 7.7 percent in the last two decades, the country is now on the verge of graduating from low-income to middle- income status. A society that was torn apart by protracted civil conflict and external aggression in the 1970s and the 1980s is now demonstrating strong social cohesion and unity. Home to widespread poverty, miserable health conditions, and high illiteracy only about two decades ago, the country has more than halved extreme poverty, achieved robust improvements in health and is close to attaining universal primary education. The country has achieved these economic and social transformations at the same time as it has embarked on a process of internally driven democratisation and decentralisation of its polity. Recognising these development achievements, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) now includes Cambodia in the select list of “dynamic” low-income countries that started their economic takeoffs in the 1990s (IMF 2013).

Advocacy Handbook: A Practical Guide to Increasing Democracy in Cambodia

Publication Year: 2003 / Sources: PACT CambodiaThis practical guide is a tool that advocates can refer to when implementing a campaign. Though advocates should not be limited to following the strategies contained in this guide and are encouraged to create your own strategies, this guide attempts to compile some of the best practices for implementing your strategy. The handbook provides guidance to advocates that are useful in checking advocacy strategies before, during and after a campaign. The first section examines the meaning of advocacy, with particular attention to the local context. From there, the guide moves into a step-by-step action plan for a campaign. Each part of the process is outlined and best practices are explained. There is also a how-to section on involving government and media. An evaluation of advocacy efforts in Cambodia describes lessons learned from past campaigns, and two case studies examine urban and rural advocacy to provide a more in-depth analysis of what has and has not worked. Finally, there are appendices designed to help with media campaigns, the legislative process and lobbying efforts.

Adopt-A-Prison Project

Publication Year: 2010 / Sources: LICADHOThis report aims to: provide a national overview of prison life and identify the key problems faced by children, their mothers and pregnant women living in prison, consider the extent to which the project has helped to meet the need for food, drinking water, clothing and basic medical care, and how to improve existing services, and consider how the project could be developed to meet the educational and recreational needs of these prisoners and their children.

Anti-Corruption Policies in Asia and the Pacific Self-Assessment Report Cambodia

Publication Year: / Sources: Asian Development Bank (ADB), Anti-Corruption Initiatives, Anti-Corruption Division, OECDIn order to gain a comprehensive and structured overview of the endorsing countries’ legal and institutional framework in place to ensure and enhance transparency in the public sector, combat bribery and promote transparency in business operations, and facilitate public involvement in the fight against corruption, endorsing countries of the Action Plan have decided to take stock of their relevant legal and institutional provisions in place. The following report reflects the Anti-Corruption Policies that Cambodia has reportedly in place as of October 2003. Organized along the topics of the Anti-Corruption Action Plan for Asia and the Pacific, it outlines the legal and institutional framework governing each of its issues, the respective implementing agencies and recent of planned reforms.

Adaptive Social Protection in Cambodia

Publication Year: 2015 / Sources: UNDPThis report is the third component of the UNDP-CO ASP initiative mentioned above. It builds on a Situation Analysis (Béné and Tech 2014) and two Theory of Change workshops (Manda and Yamamoto 2014) that were organized and facilitated by UNDP-CO in Cambodia in the months preceding the production of this Strategy Paper. Both the Situation Analysis and the Theory of Change workshops were aimed at generating useful background information for the Strategy Paper. The Strategy Paper outlines a framework (a roadmap) around which the three communities of practice in Cambodia would find practical opportunities to collaborate in the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of ASP interventions. The paper envisions a 10-year implementation horizon, while focusing primarily on major actions during the first 5-year period. Those actions include: awareness raising, identifying entry points, building capacity, learning by doing, and developing effective partnerships with government stakeholders, civil society, and development partners.

Accountability and Planning in Decentralised Cambodia

Publication Year: 2008 / Sources: Cambodia Development Resource Institute (CDRI)This paper is about sub-national accountability and planning, where accountability is the central focus and planning is considered an instrument for achieving accountability. The paper aims to understand major issues that affect sub-national planning’s ability to advance accountability and then to draw key lessons for the decentralisation and deconcentration (D&D) reform, whose main objective is to promote sub-national accountability so as sub-national planning to promote accountability has been continuously improved by the introduction and implementation of reform initiatives, most notably the former SEILA programme. Yet, planning’s ability to advance accountability faces a number of constraints.

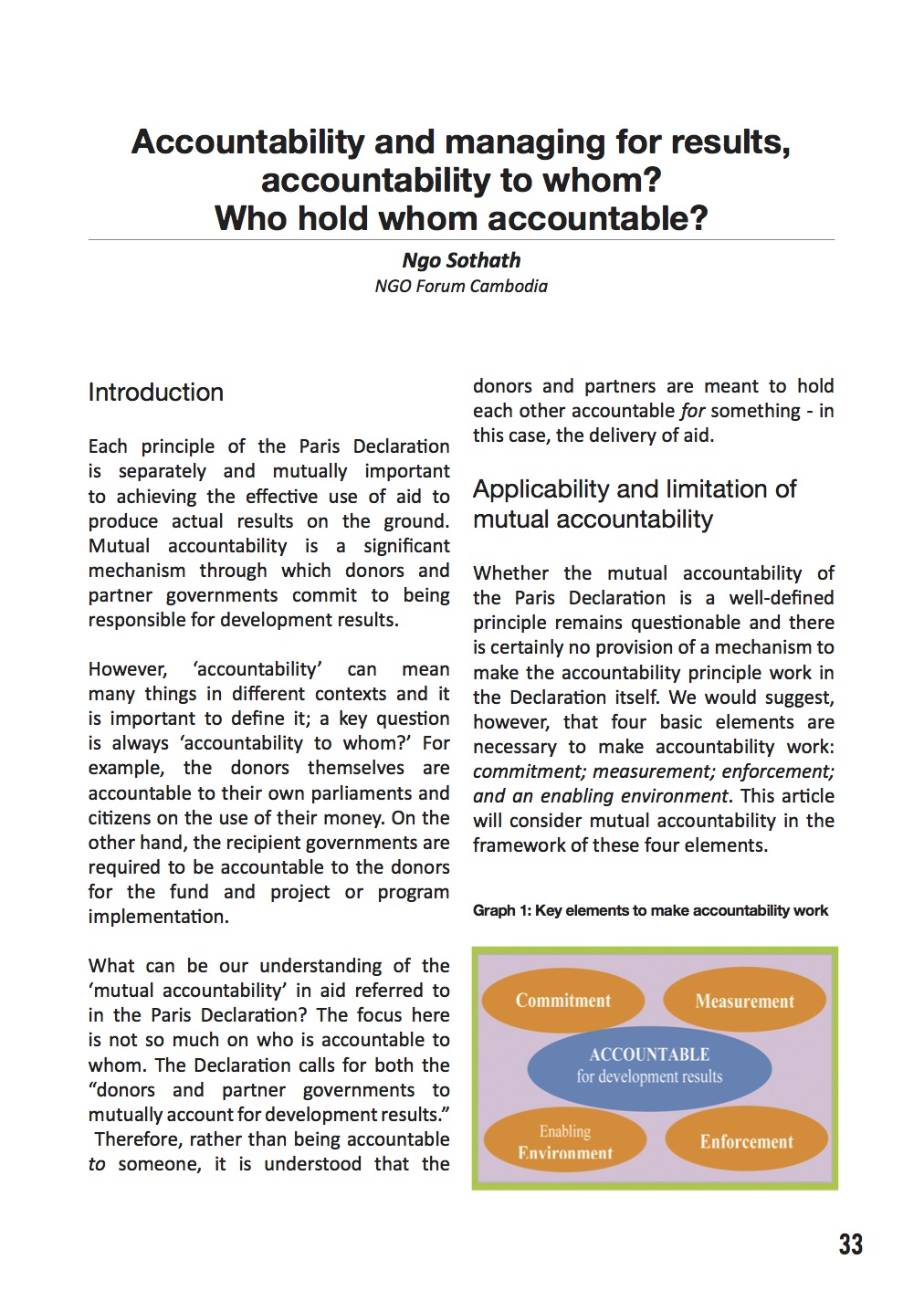

Accountability and managing for results, accountability to whom? Who hold whom accountable? accountability to whom? Who hold whom accountable?

Publication Year: ---- / Sources: NGO Forum CambodiaEach principle of the Paris Declaration is separately and mutually important to achieving the effective use of aid to produce actual results on the ground. Mutual accountability is a significant mechanism through which donors and partner governments commit to being responsible for development results. However, ‘accountability’ can mean many things in different contexts and it is important to define it; a key question is always ‘accountability to whom?’ For example, the donors themselves are accountable to their own parliaments and citizens on the use of their money. On the other hand, the recipient governments are required to be accountable to the donors for the fund and project or program implementation. What can be our understanding of the ‘mutual accountability’ in aid referred to in the Paris Declaration? The focus here is not so much on who is accountable to whom. The Declaration calls for both the “donors and partner governments to mutually account for development results.” Therefore, rather than being accountable to someone, it is understood that the donors and partners are meant to hold each other accountable for something – in this case, the delivery of aid.