Corruption and Anti-Corruption in Cambodia 2012 in review

Publication Year: 2012 / Sources: Partnership for Research in International Affairs & Development (PRIAD)Corruption continues to be systematic in Cambodia, and links-in with a number of issues, chief of which is access to valuable natural resources and human rights abuses. Many rural residents and civil society activists are locked in a fight with government over the allocation of large land concessions to exploit minerals, timber, and water resources, often encroaching on settlements and villages. Cambodian authorities, in turn, are increasingly resorting to violence to quash the protests. Land concessions tend to be awarded in shady circumstances to international conglomerates and/or local businesses that often act as front companies for tycoons or politicians. The Cambodian NGO Licadho estimates that approximately 2.1 million hectares (roughly the area of Wales) has been transferred to private developers. This is often done at the expense of local residents who are rarely compensated as well as the environment (Cambodia is experiencing high deforestation rates due to illegal logging, hydropower projects, large-scale agro-industrial ventures and entertainment complexes). A recent report by the U.N’s special rapporteur on Human Rights claimed there is no evidence that revenues from land concessions are used to alleviate poverty.

Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Cambodia, Surya P. Subedi

Publication Year: 2012 / Sources: Human Rights CouncilThe report, submitted in accordance with resolution 18/25 of 26 September 2011 of the Human Rights Council, is an assessment of the human rights impact of economic land concessions (ELCs) and other land concessions and major development projects in Cambodia (generally referred to as ―land concessions‖ throughout the report unless otherwise specified). It includes not only an analysis of concessions pertaining to agro- industry (for example, rubber, sugar, acacia and cassava plantations), but also to concessions for mining, oil and gas, forestry, and concessions for the purposes of tourism, property development, and large scale infrastructure, such as hydropower dams.

A Baseline Survey of Sub-national Government: Towards a Better Understanding of Decentralisation and Deconcentration in Cambodia

Publication Year: 2011 / Sources: Cambodia Development Resource Institute (CDRI)As Cambodia’s decentralisation and deconcentration reform moves into its second stage, it is attracting close scrutiny from policy makers, donors and academics. Adoption of the Organic Law in 2008, in line with the reform strategy of 2005, paved the way for the first election in May 2009 of district1 and provincial councils which are to improve service delivery and facilitate local government. The establishment of these two administrative layers offers communes2 the opportunity to choose the councillors from whom they demand accountability, and introduces a new relationship between commune councillors and higher councils. District and provincial councillors took office more than a year ago, yet there is no available study of their relations with their voters, the commune councillors. With long-term funding from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, CDRI – through its Democratic Governance and Public Sector Reform programme – has undertaken a survey of relations between commune and district authorities in the new arrangement.

International Republican Institute Survey of Cambodian Public Opinion

Publication Year: 2014 / Sources: United States Agency for International Development (USAID), The International Republican Institute (IRI)—

Download: English | Khmer

Country Governance Risk Assessment and Risk Management Plan

Publication Year: 2012 / Sources: Asian Development Bank (ADB)This is the first country-level governance risk assessment and risk management plan (GRARMP) for Cambodia. It has been prepared using the Second Governance and Anticorruption Action Plan (GACAP II) of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and its implementation guidelines. The assessment is risk-based and looks both at risk in relation to fiduciary matters and broader governance risks to achieving satisfactory development outcomes. The approach is based around three core governance areas: public financial management (PFM), procurement, and corruption. Over time, governance assessments of key sector risks and program and project fiduciary risks in Cambodia will be carried out following the GACAP II guidelines. The existing good governance framework (GGF) methodology (which was introduced in 2007 prior to adopting the Guidelines for Implementing GACAP II) in place for monitoring governance risks in ADB-financed projects in Cambodia is likely to be phased out. This governance risk assessment is one of the diagnostic studies prepared to inform ADB’s country partnership strategy (CPS) 2011–2013. It was developed concurrently with the CPS and discussed extensively with all relevant government stakeholders. To a large extent, approaches to mitigating major governance risks can only be successfully pursued if adequate resources and financing are provided. Thus, the recommendations of the risk assessment and risk management plan are related to future funding under the CPS.

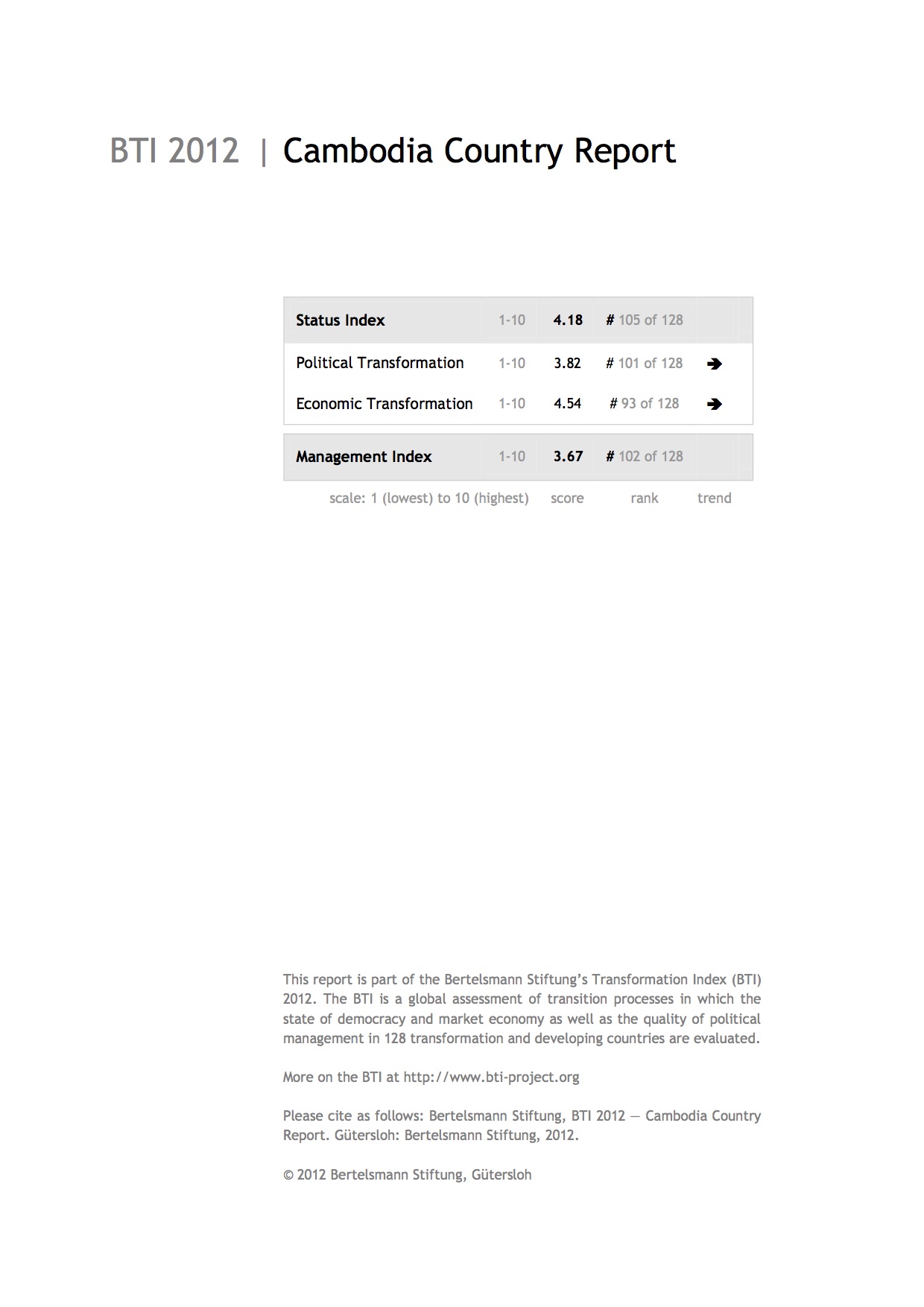

Cambodia Country Report

Publication Year: 2012 / Sources: Bertelsmann Stiftung, GüterslohThe major tendencies of the last several years continued in 2009 and 2010. The Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) strengthened its grip on Cambodian politics, further eroding the democratization process and stabilizing its de facto one-party rule. Economic growth halted in 2009 due to the global financial crisis and declines in both foreign investment and trade exports. However, the economy has begun to recover, owing to the dynamism of key sectors and targeted investment by the government. Persistent structural deficits including an unequal distribution of wealth, a growing gap between wealthy and poor Cambodians, and corruption prevent sustainable development.

Case Study Series: Buying Senate Election Votes

Publication Year: 2012 / Sources: Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR)A recent attempt by two men to buy the vote of a commune councillor in the Senate election has highlighted the endemic nature of corruption in the political spheres of the Kingdom of Cambodia (“Cambodia”) and the failure of government institutions to address the situation. This fact sheet outlines the incident, before summarising the domestic and international laws relevant to vote buying and the failure of existing domestic laws to offer protections to those who report incidences of corruption. This fact sheet is written by the Cambodian Center for Human Rights (“CCHR”), a non-aligned, independence, non-governmental organization (“NGO”) that works to promote and protect democracy and respect for human rights — primarily civil and political rights — throughout Cambodia.

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2011

Publication Year: 2011 / Sources: United States Department of StateCambodia is a constitutional monarchy with an elected parliamentary form of government. In the most recent national elections, held in 2008, the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) won 90 of 123 National Assembly seats. Most observers assessed that the election process improved over previous elections but did not fully meet international standards. The CPP consolidated control of the three branches of government and other national institutions, with most power concentrated in the hands of Prime Minister Hun Sen. Security forces reported to civilian authorities.

Anti-Corruption Strategy and Politics Five-Year Strategic Plan 2011-1015

Publication Year: 2011-2015 / Sources: National Council of Anti-CorruptionFor the Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC), good governance is the crucial sine qua non to achieve the sustainable and equitable economic development and social justice. Good governance requires dynamic participation and determination from various sectors in the society with accountability, transparency, equity, inclusiveness and the rule of law. The RGC always considers corruption as an obstacle to economic development, rule of law, democracy, social stability; and it is also the cause of poverty.

Dialogue dynamics, programming challenges: Donor approaches to anti-corruption and integrity reform in Cambodia, 2004 to 2009

Publication Year: 2010 / Sources: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI)This study aims to provide an overview of donor approaches to reforms related to anti- corruption and integrity in Cambodia over the past five years, from 2004 to 2009. It investigates the manner in which donor agencies have conceived of Cambodia’s governance and corruption challenges, the manner in which they have conducted dialogue on these challenges with government counterparts, and the programmatic means they have adopted to attempt to meet the identified challenges. It also attempts to capture some tentative lessons for future donor dialogue and programming in relation to anti-corruption and integrity reform in the country.